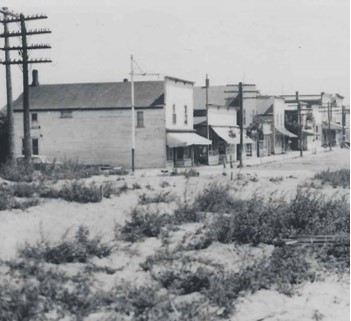

In 1929, after WWI, Wexford County was in the doldrums. The depression was settling over the area. Logging was nearly ended, and the few farmers that had stayed behind to farm the land found the wind, unchecked by the forest, gouged holes in the land, and whirled sand into dunes that slowly walked across the countryside. It was fast becoming a dying land.

Fortunately, Bill Baker, newly hired Superintendent of the Mesick School was also the agricultural teacher. He saw possibilities, whereas others only saw dried-up sandbanks. Baker a single young man at that time had a lot of time to think. What was it he thought about? What was it that this backwoods village of 360 folks, living in unpainted homes could do to survive?

“His first step was to start a nursery on school grounds. Within 2 years the seedlings were ready to plant. Second, he and his Ag boys began transplanting the seedlings on the barren nearby hillsides. This was a part of education was it not? How to keep the community’s most basic resources? It was a start. With that underway, they also wanted to be proud of their school. So, they began to move sumac, dogwood, and cedar from the forests and lilac bushes from abandoned homes to landscape the school grounds.

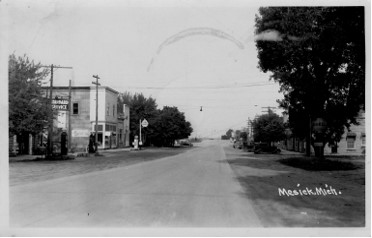

‘The next thing that happened the town begin to take notice. Landscaping began around town and homeowners began painting and sprucing up their buildings. Maple trees sprang up along main streets, side streets, and back streets. Before long, landscaping was taking place for miles around. There was hope that someday things would get better.

‘Thoughts on what else could be done to make the land better began to develop, and whenever ideas were afloat you could always find Bill Baker. Farmers around Mesick began to have questions answered. They met to form one of Michigan’s first farmer co-ops. And why shouldn’t local farmers be growing gladiolus bulbs for the market? The bulbs would grow fine and big too in the mellow sand. The trouble was they needed an honest market to consign them to. Students sent invitations to growers to meet with specialists from the State College. The result was a marketing co-op that had members all over northwestern Michigan. Baker thought that was the kind of leadership and community service his school and students should be involved in.

‘In the 1940s the depression hung on and businesses folded. When the local printing shop folded, the school bought it out for less than $2,000 lock, stock, and linotype. The pupils started a newspaper for the parents to know every move the school was making—since the school was the center of most of the community happenings. English classes benefited because instead of make-believe exercises, pupils drafted letters, petitions, memorials, or about anything anyone asked. Handbills for auctions? They drafted and printed them and pocketed the profit. Did kids learn grammar and spelling that way? You bet they did. No one wanted their mistakes to parade in public.

‘Early on when Bill Baker come to Mesick and the lumbering was dwindling, a lumber company was letting a 1,500-acre tract go for $.50 an acre. The Superintendent and Board decided to gamble on buying it. Later on, when the village needed a Health Center, the logs were taken from the school forest by helpful students and community workers. Not only did the school forest furnish the logs, but the rest of the grades, Kindergarten through 12th grade also caught the spirit. They donated funds through paper collections, fish suppers, school store, and bake sales. And then one day the Health Center got built. The school board president commented, “Darndest guy we ever saw, nothing can stop him and those kids.”

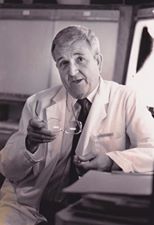

Plans that were made for a Health Center in 1948 were finally accomplished in 1950 and just in the niche of time as Mesick’s long-time doctor, Dr. McManus passed away. Other very early doctors were Dr. H. Dwight Griswold, the first Sherman Doctor who also served Mesick; Dr. Edward Morgan; Dr. John Fordyce Gruber, the first Mesick Doctor 1903; Dr. Albert E. Stickley, the second Mesick Doctor (before 1910); Dr. Edwin A. McManus, second Sherman Doctor -1894 and third Mesick Doctor 1906 -1948.

Once the Health Center was built it was served by many doctors over the years: D.E. Boblitt MD, Dr. Steel, M.D., Dr. Peterson, M.D., Dr. Robinson, D.O., Dr. Hackett D.O., Dr. Vicki Manzanno D.O., Dr. Vander Roost, D.O., Dr. Vander Hagen, D.O., and Dr. McNinch, D.O. Dr. Cody Smith and Dr. Charles Krammer was lost to the draft after serving very short terms in the early 50s when they were called to serve their country.

However, getting back to Bill Baker and the school, “parents liked the idea offered that you learn by doing. Time after time Mesick kids learned that they did not need to depend on someone else; they had power themselves. You might ask if Baker was more interested in school or community. The answer was that the more you serve one the more you serve the other. The cannery, supervised by the school janitor was busy all year. Parents put up their year’s fruits, vegetables, and meats in the community cannery while visiting with the neighbors. Further, the school’s home economics class benefitted by learning modern canning methods. Besides, the products were used in the school lunchroom. It was a win-win situation.

‘By 1950 the Mesick School enrollment had increased to 590 students. All this is in a district with a $4,000 taxable value per child. Nevertheless, with all this, how about the 3 Rs? Doesn’t the pupil come out short when he is running about doing this, that, and the other? Studies of Mesick Schools pointed to one answer: children there were learning their basics. As a matter of fact, University of Michigan researchers found Mesick school students were excelling in reading, arithmetic, and spelling.

‘Bill Baker thought it a wasteful shame to build an education for the one-fifth of the students that would attend college and forget the other four-fifths that would make a living on what they learned in high school. At Mesick, students were allowed to pick their own courses in a field they would choose after high school and pre-college courses were made optional. Dropouts lessened with his method.

‘Top honors were given on the basis of service to the school, community, teachers, and students. Not just top athletes received coveted “M’s,” but everyone who earned 150 points in community service. Young folks learned to get along well with people because they had a lot of practice. They got things done. And, somehow, they were leaders.

‘A community can afford to pay a man well who pulls the whole area out of the doldrums. With help from a local committee, Baker succeeded in getting a glove factory to move into town and encouraged skiing for the youth once the hill was cleared through some challenging work of young and older folks alike. A German educator who wrote back home after visiting Mesick said, “The schools here are far different from ours. Here they belong to the community, not to the state so that a community can have as good a school as it wishes. And in Mesick,” he added, “the community wishes a very good one.”

Because of the methods used at Mesick Schools, Columbia University collected data to train a different kind of educator, one not confined to the narrow field of classroom supervision.

*Excerpts taken from April 1956 Farm Journal Magazine. Author Richard C. Davids.

Gallery